Nancy Rabalais dove off a research vessel, and with a splash of her flippers she disappeared into the water. Beneath the surface, fish darted past her in the shimmery green landscape. As she sank deeper, beams of sunlight overhead dimmed and signs of life disappeared. Rabalais, a marine ecologist, has monitored the dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico for 35 years. Each summer, she and a team of researchers embark on a Shelfwide Cruise to map the hypoxic, or low-oxygen zone off the coast.

Urbanization and agricultural expansion in the Midwest fuel the increase in nutrient pollution in the Mississippi River watershed. Louisiana is only a small contributor to this issue, but the state witnesses its effects firsthand.

Toxic blooms are appearing in Lake Pontchartrain and the dead zone looms nearby in the Gulf of Mexico. “Now, you can’t see it from the surface of the water. You can’t see it in satellite images, so how do we know it’s there?” Rabalais said during a Ted Talk in New Orleans. “Well, a trawler can tell you when she puts her net over the side and drags for 20 minutes and comes up empty, that she knows she’s in the dead zone.”

Annually, the Mississippi River collects roughly 10,000 pounds of fertilizer and raw sewage pollution from 31 states and parts of Canada, a release by the Mississippi River Network states. The green and murky underwater world Rabalais dives in is the result of the high concentration of pollutants that flow down the river and into the Gulf of Mexico. The Mississippi watershed spans 3.2 million square kilometers across the central United States. As the water travels south through the agricultural land of the Midwest, it collects large amounts of runoff. High nitrogen and phosphorus loads seep out of the mouth of the river and into the Gulf of Mexico. Excessive amounts of fertilizers combined with rising water temperatures can create extremely low levels of dissolved oxygen, either killing or dramatically reducing the populations of fish and other aquatic organisms. This happens when sudden high nutrient concentrations stimulate the growth of tiny microscopic plants called phytoplankton or marine algae. When the algae become too abundant, they die and sink to the bottom. As the algae decomposes, bacteria eat the dead matter, using up the oxygen in the water column. The resulting dead zone, devoid of enough oxygen to support marine life, is empty.

This doesn’t necessarily mean fish, shrimp or crustaceans die, Marine Advisory Agent Brian LeBlanc said. “But organisms move away from these oxygen-poor zones, and there’s massive areas where there are not as many commercial species readily available,” LeBlanc said. The dead zone costs U.S. seafood and tourism industries nearly $82 million each year, a recent National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration estimate said. The impact can be devastating to Louisiana’s seafood industry. This phenomenon isn’t limited to the Gulf of Mexico. Lake Pontchartrain is a small-scale example of the detrimental effects unmanaged nutrient pollution can have on an ecosystem. The frequent opening of the Bonnet Carré Spillway floods the estuarine lake with freshwater and high volumes of nutrients. In the right conditions, webs of green swath the surface of the water.

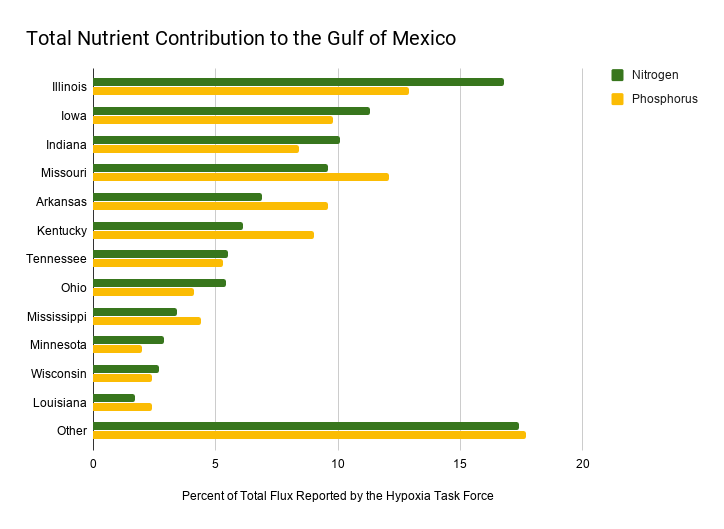

Solutions exist to address these pollutants upstream at the source, but nutrient pollution is difficult to regulate due to the river’s size. Prevention must be viewed on a larger scale. Of the total nutrient load flowing into the Gulf of Mexico, only 1.7% of the nitrogen concentration and 2.4% of phosphorus come from Louisiana, the Gulf of Mexico Hypoxia Task Force reported. Comparatively, Illinois, relying heavily upon agriculture, contributes 16.8% of nitrogen and 12.9% of phosphorus. “When you’re sitting here at the bottom of the watershed like we are in Louisiana, it would be helpful not to have to deal with this directly and have everybody work together to remediate this problem,” John White, a biogeochemical researcher said. “But unfortunately, we have state boundaries and need a federal program.”

According to the Environmental Protection Agency, the primary sources of excess nitrogen and phosphorus are agriculture, runoff and domestic and industrial wastewater. Management practices such as buffer strips and increasing the distance between agricultural fields and streams can provide barriers for high nutrient runoff. But once the nutrients enter the water they are expensive and difficult to remove. Fertilizers are applied to plants to help them grow, but when it rains, the runoff carries the excess fertilizer into the nearest stream. This water eventually flows into the Mississippi but starves the surrounding wetlands of the nutrients they need to survive.

White described the southern Mississippi River as one long pipe. The continuous levee system on both sides prevents the river from carving the land and flowing off path. Historically, the annual flood pulse of the Mississippi had supplied surrounding wetlands with freshwater and nutrients. Wetlands conduct natural processes that remove excess nutrients from the ecosystem. “If you take that river water and you push it into a wetland, the nitrogen will enter the soil,” White said. “Microbes then breathe it in and turn it into harmless nitrogen gas, expelling it back to the atmosphere.” The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers designed both the levee and spillway systems solely for flood protection of the surrounding low-lying areas along the river without considering the environmental consequences of its construction.

The urbanization and development of areas along the river will continue to worsen this issue. As the U.S. population continues to grow, so will its dependency on agriculture. LeBlanc works with farmers to develop better management practices, but the problem of wastewater dumping still remains unsolved. Sewage from heavily populated cities along the river still discharge large amounts of wastewater into the watershed. “It’s not just the farming community that has to adapt, it’s going to take many sectors of the population that live along a river to adopt new policies,” LeBlanc said. “And it all comes with a cost.” Creating advanced wastewater treatment facilities and management policies could force the cost of food upward, ultimately costing the consumer more, LeBlanc said.

A solution will take the cooperation of cities and urban areas along the lake to mitigate the effects of nutrient pollution. The Old Man River will continue to rush 2,318 miles across the country, sweeping runoff from the land with it.

The future of Louisiana waterways will remain grave if no action is taken.

“They always make it seem like you can just do one thing and solve the problem,” White said. “But economics is tied to the environment, which is tied to people and agriculture, and energy, and everything. You can’t move one piece and not expect everything else to change.”